The act of weight training is

governed by a multitude of factors. Of great importance is the biological

factor: our physical response to training. Within this factor are multitudes of

smaller factors, each contributing to the goal of getting bigger and stronger. Understanding these small factors and knowing

how to manipulate them is how we grow. So we are told by the science-based

advocates in the gym community.

Jeff Nippard, Mike Israetel, Layne

Norton, and their ilk are the titans of information within the fitness space.

This is because many of them are experts in this realm and provide good

information while at the same time being entertaining and skilled

communicators. Their content is often helpful, and due to the constant churn of

academic publishing, their content is endless. If they are big and strong, it

is even better. All it takes is an educated and entertaining individual to read

a study and interpret its results in the most helpful way possible.

.jpeg) |

| If Mike can't laugh at this, bless his heart. |

Is that not what we see time and

again? A study is published. Its results are echoed across social media by

every science-based influencer. The impact or effectiveness of what the study

supposedly proves is exaggerated for a while. Then follows a brief period of

walking back those claims. Followed by a new cycle of science-based echoes

whispering in every gym of what is now optimal. Such is the case of lengthened

biased training we see now, and very slow tempo training before it, the now

often heckled “functional fitness” era and so many other previous training fads

that were in their day dressed in science.

The logical objection here is that today’s

science-based is true whereas bygone cycles of information was “bro-science.” While

there is some validity to this objection, do not forget that such bro-science was and still is, misinformation based on misunderstood or misapplied scientific

principles. Time under tension, for example, became exaggerated to the point of

being the supreme training factor because bodybuilding and personal training industry leaders at the time dramatized

its importance. Whether intentional or borne out of science illiteracy it does not matter, for the result is the same: what is heralded as the next

scientific breakthrough is claimed to further optimize and therefore quicken

your results. Not only that, but refusal to accept this breakthrough and

implement its methods is seen as anti-science, and therefore stupid.

This remains the status quo until

the next breakthrough that creates the next cycle of scientific optimization. Parallel

to this new cycle runs the death of the old. With enough time that old science

becomes forgotten or is exiled to the island of bro-science. This birth-death

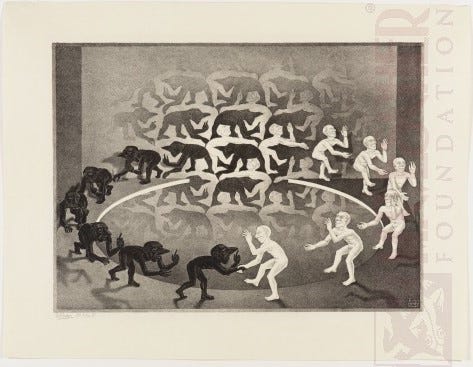

cycle of science-based training has repeated enough times in my life that the

pattern is now seen clearly, knurling the scales of an ouroboros. What was once believed

to be of utmost importance is eventually consumed and forgotten by the process

of discovering and inventing new things of importance.

|

| This, but a barbell. |

Today, a sense of disenchantment is

washing over the lifting community. The cycle of science-based information has

quickened. A new study is pumped out and promoted weekly, it seems. The rate of

information and exaggeration of its importance are the two primary causes of

the disenchantment felt today. It is becoming impossible to keep up with all

the newly important factors that govern how our bodies respond to training.

Therefore, when such important factors are not carefully practiced and adhered

to, and novel factors not learned, understood, and implement, then our training

eventually becomes “suboptimal.” Why then waste our time? Why then risk

becoming the stupid one in the gym?

The issue is becoming clearer. It is

not science itself that causes this problem. Far from it. Scientific principles,

the big things, should always govern our training. No, it is not the science

communicators that are the problem, either. Many are qualified experts. Much of

their content is valuable. And while there are a few bad apples, and unfortunately

some good apples go rotten, I am confident that much science-based information

is mostly helpful. Their first problem is overreliance on new information to

justify their actions and results. For there will always be new information,

such is the nature of science, but there will not always be new results. This

divergence is unavoidable. It leads to disrepute.

Additionally,

these kinds of content creators are often merely interpreters, and in many

cases, poor ones. Can this blame rest entirely at the foot of the consumer of

this information? Not when even the supposed good apples are putting out videos

with titles like “Get Abs in x-Days” and “The Perfect Program for x-Muscle.” This

content is gimmicky and, in many cases, superficial to the point of misinformation.

Nowadays it comes across as a grift. These influencers rely on scientific

jargon, a pile of studies, and when applicable, several letters after their name.

|

| This is a grift (According to Science) |

The

foundation of this problem is materialism and with it the seeking of knowledge

(which becomes a thing when we present it as an object, a fact, a datapoint to

our reasoning). This is an old problem that existed long before gyms. This

problem is cross cultural and ancient. The problem with such an approach is not

simply materialism itself. No, the problem is using materialism as the basis

for what must start as and always be a story. At its core, this is the battle

between how versus why. While how governs why, there is no how without why.

This

is not to say that scientific materialism has no place in training. Far from

it. All I am saying is that science-based training would serve better as the

sidekick than the hero. The whims of the sidekick change so frequently as to

detract from the mission. This is always the case. The hero, knowing the faults

of their sidekick, puts them in places where they are most valuable and likely

to succeed. So too you should place the science-based influencers beside you.

Then you can further your story and accomplish your mission, being the hero you

are.

As

I see it, this is the only viable option when it comes to training longevity

and therefore long-term results. Knowing what mechanisms of action are inside

the muscle fibers is not going to create six-pack abs. Likewise, big arms do

not come about by knowing electromyography data and basing exercise

selection entirely on that information. Such will not guarantee 20-inch arms.

The only thing that brings us closer to nice abs and big arms is the process

itself. While that process does rest on a multitude of scientific principles, those

nuances are themselves less important individually, and as a whole, only

moderately more important. Does your next workout rely on the next study? Do

your results next year rely on data yet published? Of course not.

|

| If only he had the benefits of modern science. |

What

produces results is the day-to-day creation of our own story. This story, your

story, is a process aided by science. But it must have more philosophy and

artistry than is commonly espoused today. In fact, it is fair to say that such

elements of training are underrated and even hated by the science-based crowed just

as much as “anti-science” lifters deemphasize scientific principles in their

training. When it comes to getting big and strong, knowing the how is far less

important than committing to your why. Does having data in mind make commitment

easier by being more confident in your choices? Sure, it can. But understand

that choice, for nearly every consumer of science-based content, is more akin to faith than knowledge.

|

Have faith in Dr. Seedman,

for he too claims to be science-based. |

The root word for "confidence" comes from the Latin word

"confidentia," which is formed from "con-" meaning

"with" and "fidens" meaning "faith."

How

much information about training is needed before one calls it enough and takes

the leap, confident in what they have learned from the science-based experts?

That is individually dependent, of course. So, consider this: if you forgot everything

you knew about how the body responds to weight training, would you still go to

the gym and lift weights? I would wager that most of you still would. This is

because we value training for the process and the results. The story written with each rep. Not what new factoid we learned about muscles.

Even

the science-based influencers themselves are beginning to rely on their own story to bolster their information. Story lends credibility just as much as

peer review. It sounds false, and sometimes is, but in the gym – such is not

the case. Watch how the science-based influencer elevates the importance of a

new study by ending videos with “and this is how I will incorporate this new scientific

information into my training.” Their story is the capstone. Their commitment to

this new information increases its perceived usefulness to the viewer, who then

also changes their training to accommodate this new information. As this cycle

continues, both the viewer and the science-based influencer commit not to a

scientific approach, rather, they have unintentionally committed to a story that

is distinctly anti-science.

|

| "One weird trick (SCIENCE!) to make your arms blow-up!" |

Let

me explain. Science-based influencers create for themselves and their audience a

problem that is intrinsic to their worldview. Every new datapoint must be

considered and implemented (so long as it is peer reviewed). With an endless

stream of new information describing increasingly tiny biological details, which

are then incorporated into a new training plan, these lifters develop training Attention

Deficit Disorder. When not that, the classic “paralysis by analysis” persists. Because

of these things results are stymied. But why? The answer is simple. Always changing

how one trains is not a scientific approach. In fact, it is the opposite. Controlling

variables, single factor changes, observation over various lengths of time; these

things contribute to a scientific training approach. But unfortunately, that is not how

science-based lifters nor the influencers themselves train. Because if they do,

they fail to incorporate the “new science” fast enough, risking becoming

irrelevant and losing value in the market where their story is told.

How

much bigger and stronger this year compared to last are the top science-based gym influencers? In prominent cases, not much, or at all. Their competitive results (or lack

thereof, due to non-participation) have not improved their professional

standing despite the breadth of their training information increasing. A lab cannot not build a physique, but a story can. Even with the very best

information and access to equipment, a lifter cannot build a competitive physique or strength without first having a reason to do it, their why. Then, committing to that story.

|

New science on the left.

Old science on the right. |

This

is where highly successful lifters, whether competitive strength athletes or

bodybuilders, depart from those who fall short. While science should be incorporated,

for it does govern basic biological processes, it does not compel us into the

gym like a story does. Becoming who you intend to be, fulfilling your destiny, chasing

the impossible, breaking records, being the best of the best… however you frame

it, this worldview is what fuels motivation, generating momentum, bringing

about results, merely an anecdote to some – but everything to one, you.

For

these many reasons I must place myself firmly in the storytelling camp. For

that’s all there is, practically speaking. But I will not call every science-based

influencer my enemy. No, they are simply lost and will return to the

flock after being taught the real value of the why. They must be shown that when

they summarize or exaggerate studies to the point of misinformation, they defame themselves and

their comrades of the science-based worldview, making them and their

storytelling approach less desirable. This is one way that good apples turn bad. Another is presenting a façade of science while not training as they promote. In these cases, performance enhancing drugs are typically being used because steroids are the botox of poor training. We see these things in social media every day.

Sadly,

the death of science-based lifting will be self-inflicted. Exaggerated and

false claims about studies produce none or at best lackluster results. How long

before the next optimization scheme is presented, adopted, then abandoned? When

the leaders of this worldview present manure, the stink pushes away their

audience. This, coupled with cold-hearted algorithms that favor frequency over honesty,

forces the endless churn of increasingly pointless science-based content. The social

media machine turns faster and faster, requiring more and more content, which

the scientists themselves cannot keep up with. So what then is the science-based

influencer to do? Rehash and reemphasize old information while exaggerating

their own results. Telling their story, a science-based tall tale.

|

| A star-studded cast. |

The clashing of these two worldviews, that of

science-based lifting and that of storytelling (anecdotal evidence), is not

necessary. Unfortunately it seems inevitable. Just this year we saw an “anti-science” brute assault one of the science-based figureheads, Jeff

Nippard. Mike Van Wyck shoving Jeff to the ground in a gym was the shot at Fort

Sumter, signaling that war between these two worldviews has begun. I do not

agree with Mike’s means of communication. For him, it was all he could articulate

from his position on the battlefield. Here he was, a soldier of small importance

placed in striking distance of an enemy general. I understand this. For Mike’s

story, he was compelled to act in that moment. Too bad he was incapable of communicating his position, thus making him the bad guy and Jeff good, forever. But what happened beneath the surface? People started

noticing how poorly the science-based camp has been operating.

Now

the rift spreads further. Science is under attack at the gym, literally in Jeff’s

case. Figuratively in every other case where lifters are seeing Jeff and his

comrades walk back one claim after another, thus beginning the process of forgetting them and their content. When science-based influencers forget their misinformation and exaggeration,

or deny it altogether, they lose credibility and so battlespace. This is

worsened by their need to create content to stay relevant.

Compared

to the science-based influencer, the storyteller does not have this problem.

Their credibility depends only on their results, and if they are a coach, their

clients. This credibility can only be destroyed by dishonesty. Or in Van Wyck’s

case, stupidity. Apart from that, an honest storyteller, knowing what scientific

information is useful, will properly implement it so that their story is

successful. In doing so, science-based training lives on… in the storytellers.

|

| If only he could. |

This

is the choice these science-based influencers have: Either continue the charade

and risk irrelevancy and credibility due to exaggerated and sometimes false

claims, while at the same time risk falling to the wayside in the violent churn

of the algorithm. Or choose storytelling by emphasizing the philosophy and

artistry of their training, bolstered by honest scientific principles.

By

choosing the latter, today’s science-based influencer will not only survive, but

they will quickly attain even greater authority than currently achieved. Best

of all for this camp, they perpetuate genuine science-based lifting without qualm.

They tell their story with science as the sidekick. Showing you how to make it

your own. As I have tried doing all these years.

May

your training bring you to new heights. Happy New Year.

Edit: Since the publication of this post, one of the best fitness storytellers, Will Tennyson, earned his bodybuilding pro-card. I highlight that fact not as proof of a prediction, but rather, additional proof for my position.

.jpeg)